(Had the pleasure of sitting down with theater actor, Jef Flores. We talked about his career as well his latest play, In the next room or the vibrator play

. The interview originally appeared on GIST.)

*

Don't call Jef Flores an award-winning actor

“You have permission to slap me in the face if I turned into a douchebag,” actor Jef Flores asks us to mark his words, so here it is on record.

He has every reason to fear it: since making his debut in professional theater five years ago — without any training, save for doing improv and being a musician back in the States where he grew up — Jef has been cast in some of the most successful productions by a diverse set of theater outfits, and in 2015 snagged a Philstage Gawad Buhay Award for best male lead performance in a play.

His latest gig: artist Leo Irving in Repertory Philippines’ In the Next Room or The Vibrator Play. The title may well be a marketing ploy, as Sarah Ruhl’s tale, though billed as a comedy, reads like a domestic drama. New York, post-Civil War, dawn of electricity. Here the vibrator is purportedly used as a medical tool to cure hysteria. The women discover its non-medical wonders. And so does one man. Leo.

“They needed an out-of-the-box guy. The artist character has to be colorful and have this ambiguous sexual energy,” Jef muses on why he was called to read for the role. “People find it difficult to pin down my sexuality, which is very clear-cut as far as I’m concerned.”

But why pin him down when it’s so much more fun to watch him be. This soft-spoken mama’s boy loves boxing, to begin with, and has dreams of becoming a power metal singer (lost his shit at a Dragonforce concert). He’s among the few who still evolve Poliwags in Pokémon Go (Level 33 as of this writing). Give him coffee and the slightest nudge and he’ll tell the craziest stories (once he played Snow White’s prince charming and, in a real-life plot twist, became the one who needed waking up backstage, thanks to insomnia).

Jef is also disarmingly honest. He’ll be the first to say that sometimes he gets the job because of his so-called face value. And sometimes he doesn’t because his Tagalog sucks. Here he is talking more about work — how he landed in Philippine theater, his orgasm problems in The Vibrator Play, and why he keeps his Gawad Buhay trophy inside the liquor cabinet.

|

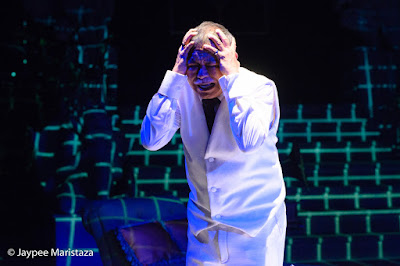

| Jef Flores as Leo Irving |

GIST: You’re everywhere. Never running out of jobs. Where did it all start?

JEF FLORES: I was a musician and a performer in the States, but those things weren’t coming to fruition. So my cousin told me to check out the music scene in the Philippines. When I got here it turned out that there was music, there was art, and the theater scene was seeding something. Repertory Philippines took me in and started me off in Camp Rock. In my first month of just poking around, I was working with Rep, walking for Bench, and got a commercial. Then Resorts World started doing theater. I was one of the boys in toga in Priscilla (Queen of the Desert), but I had no mic, because I was one of the weakest singers. When people go, “Oh look how far you’ve come,” I’d say, “Yeah I have a mic now.” (Smiles) It’s nice to be heard.

Where did you learn how to act?

Everything that I know how to do has been taught to me by the directors who’ve been forced to deal with me. Bart Guingona is definitely a mentor of mine, as is Michael Williams — being with him in Resorts World, I learned so much. Most of the skills I have today also stem from being caught in between Baby Barredo and Bart in 4,000 Miles with Rep. I’ve never done a straight play before. Bart worked me and, as a co-actor, (Barredo’s) not taking any non-sense from me. It was like having the angry lola and the father figure. They were both raining brimstone on me.

You won a Gawad Buhay award for Red Turnip Theater’s This is Our Youth. What does that mean to you?

Whatever. Of course it’s an honor. But I keep the Gawad Buhay award in the back of my liquor cabinet, behind a Johnnie Walker because I don’t want to think about it too much. Once I had it I was afraid that I was setting myself up for a steep fall. Because the only reason I work so hard is that I’m just an actor. And I’ll always like to be just, simply a working person. Because once I become an award-winning actor, then my work’s going to suffer. It’s going to get into my head. It will. Because I’m that kind of person.

You have a big ego?

I’m at this war with myself where ego is important, but — how to control it? The people who are the best at what they do know that they’re the best. Floyd Mayweather has figured out boxing, but he’s a jerk. I’ve been trying to “claim it” but at the same time I’m on an active campaign to keep myself in check.

What’s the harshest criticism you received?

(11-second pause) Ricci Chan. But he has standards, and that’s what’s beautiful about him. I was helping him with the One Night Stand cabaret at 12 Monkeys. We were having a production meeting with Mahar Mangahas. They needed a line-up of six singers, and they needed a guy. Mahar said, “Why don’t you get Jef?” And Ricci went, “I need singers.”

Most annoying audience reaction?

When they laugh at the dramatic, beautiful stuff. (To an imaginary audience) I’m trying to be deep here!

Is it their fault or the actor’s?

(Before we could finish the question) No it’s their fault, they’re weird. People in general laugh when they’re nervous and uncomfortable, and sometimes we work really, really hard as actors to put them in a place, a thought that they don’t like to go to. It’s great when you work up to that moment and they go with you. But you can kind of see them stop at the door when they laugh at you.

What were your thoughts after reading Sarah Ruhl’s The Vibrator Play?

It’s sneaky. It can make you re-think how you want to spend your time. It kind of floats by, and the people who are paying attention will find themselves a little shell-shocked by it.

How did it make you “re-think how you want to spend your time”?

There are a lot of things in the play that talk about life versus technology. Being in it made me think about how addicted I am to the internet. I’m trying to make a career out of being an artist and supposedly you need to have social media working for you — and I don’t care about those things, and so I’m trying to care more about that; but at the same time I’m like, “No, you’re going to ruin your life that way, you’re already Facebooking too much.” Those things have been opened to me in The Vibrator Play. It’s about electricity versus human warmth. This has been driven into the ground: we’re more connected but also more disconnected than ever. And it’s true. I don’t know how to pick up girls — swipe right?

The Vibrator Play is saying, you know, people are real.

Ruhl is very specific about the sound that the characters make when they’re having an orgasm. She doesn’t want it clichéd. How do you guys know when you’re doing it right?

We’re leaving it to (the director) Chris Millado to guide us to that orgasm that fulfills the need of the scene. He’s arching each and every orgasm in such a way that we are telling Sarah’s story. It’s not enough to go up there and say, “Oh, I’m having an orgasm!” (We) need to go through this particular experience, it’s like a monologue.

I’ve been having issues with my orgasm, actually. Chris comes up to me, and he’s like, “Jeffrey we’ve got to work on that.” So we’re all finding it still. We open in (a week). I think it’s going to be a good orgasm.

Who is this play for?

Repressed people (laughs). The people in this play are having orgasms and they’re super apologetic about it. They’re working so hard to be proper. If you are the type of person who doesn’t want your partner in bed to be so polite, you watch this show.

As someone who didn’t plan on becoming an actor, do you see yourself in theater for the long haul?

Yes. At first it was like, step-by-step, day-by-day. And at some point I got really obsessed with it. I don’t see myself anywhere but here. I can’t be a commercial model. I can’t smile and eat crackers. Not after this.

Talk about that moment when you felt, “God, this is so good.”

It was Camp Rock. When we did our curtain call and 800 audience members stood up, cheering. They had the best freakin’ day. I had issues in high school because I was so worried about what I was going to become. That my parents would never be happy with me. I just wanted to be accepted, get a little praise. It’s nice to be in theater because when you do a good job, people clap. And they say, “Hey, we see you.” It’s nice to be seen.